- Home

- Louie Anderson

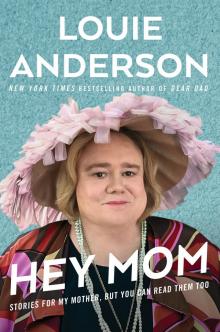

Hey Mom Page 6

Hey Mom Read online

Page 6

Playing Christine Baskets has helped me appreciate you in new ways, like the restraint and the optimism and the stress and the care you expressed or endured every day of our lives, every day of your marriage, every day of your life as mom of so many children. Christine is so aware of her faults and also of her strengths, and you were like that, too. I want to think I’m like that but maybe that’s for others to say, not me.

Jonathan Krisel, our brilliant director, said about Christine, “You feel for her and the family she was dealt.” Is that how you felt, Mom? I wonder. It sounds as if that could be true of you, though you probably would never have put it that way.

When the show finally airs, I really think people are going to love the character. I hope people will relate to her because they will see in her their own mom or other moms they’ve been around.

Mothers are artists, in their way, wouldn’t you say? They’re like symphony conductors of entire lives. They’re painters or sculptors. And not only is it really hard to shape clay into something really good, but that piece of clay is changing dramatically, all the time, even if you never touch it. A painting won’t get painted if you just leave the canvas alone but a child will still develop into something even if you neglect it. Each mom and each dad has to adapt to what they’re trying to make, hoping to make, and Mom and Dad also have to let that child turn into the creation he or she wants to be. Oh, and then lots and lots of moms and dads have to do this with two or three separate creations, simultaneously. Or, in the case of you, Ora Zella, with eleven creations. How is that not way more impressive than anything a great painter does? Picasso, Shmicasso.

Eleven masterpieces, Mom. That’s what you made. You made them with love, care, and kindness. You gave them everything you had. You squeezed every ounce of paint out of your paint tube, used every bristle on your brush to make our lives more beautiful, more visual, you gave us depth, you gave us color. You gave us foreshadowing and texture. And, Mom, sometimes I think you didn’t leave enough paint in the tube to complete the masterpiece that was you.

Jonathan also said of Christine, “Movies and TV aren’t usually about that type of woman—someone who gained a lot of weight and had a family, and it didn’t turn out that great.” That’s another reason people are going to fall in love with the character, I think—she’s so real. She looks like so many people we all know. She’s built like so many people we all know. And if people don’t know a bunch of middle-aged or older women and moms who look like Christine and who are built like Christine, those people really need to look in the mirror and figure out what choices they’ve made in their lives to deprive themselves of that. They should head downtown to any city anywhere in America right now and just sit on a bench and open their eyes. They won’t have to wait more than ten minutes before Christine walks by. Probably more like two minutes.

Here’s Jonathan again: “There’s so much annoying shit that people have to do just to get through the day—it’s a struggle. You have to think, Do I have my medicine? Do I have my stuff? . . . People get excited about their cell phone plans, too—they get excited about getting a deal, and Christine is that kind of a person. She gets excited about deals, and she’s got a garage full of stuff. Maybe it’s an American thing.”

Mom, you loved a deal. The 88 Cents Store. The 99 Cents Store. Two for ones. “Look at these, Louie, two for one! . . . three for one!” It didn’t matter if it was crap. You loved anything that was marked down. Don’t we all! If you could have found something that used to be seven hundred dollars and now it’s a quarter, even though we didn’t want it or need it . . . you would have been in heaven.

But you are. Never mind.

I love Christine. Maybe she is quintessentially American. I love that she can say, “I am in between sizes right now.”

Mom, the show has amazing writers—but if I’m being completely honest, since I’m the one playing Christine and dressed up as her, every now and then, on set, often in the middle of shooting a scene, I will tell Jonathan or the writers what I think Christine should say and how I think she should react. And they let me. Because they know it’s right. Jonathan and the writers don’t mind—their ideas are there in every scene, so as long as we keep the basic content intact, it’s fine. I just want to put a little bit more Ora Zella Prouty and Ora Zella Anderson and Louie P. Anderson and maybe even a little Louis W. Anderson in there, too, along with a helping of Mary and Rhea and Sheila and Shanna and Lisa Anderson.

You know what I wonder? When I think of you as I play Christine, which age and stage of you am I channeling? Is it you as an older woman, nearing the end of your life? You when I was just a little boy? You when I was a young man? You as I think you were before I was born? Are those yous very different?

I think I’m playing you as a whole. And think what an advantage I have. Not only am I sixty-two but you were seventy-seven when you died so that’s 139 years of experience. Could I possibly have added that right? . . . Yes, I did. One hundred thirty-nine years to draw on.

I think people will respond to Christine because she represents a kind of reverse cool—she’s so obviously her own person, doing things on her terms, whether it’s bargain shopping at Costco or baking or housecleaning or trying to clean up the mess her sons keep making. I have also given Christine an energy, a feistiness, that I hope viewers will respond to. She’s trying to take control of things. After all the heartache she’s suffered, and at this point in her life, how can she possibly have the energy to do that? How is she not too exhausted by the very thought of that?

How? Because that’s what you were like—that’s how. Your humanity and empathy were big enough to form the sixth Great Lake.

The best thing about Christine’s character, Mom? She gets to twirl. I don’t mean twirl hair. I don’t mean dance. I mean she gets to be alive.

The show premieres in late January. I have a bunch of Baskets media coming up. I’ll write soon.

You live in me and with me every day,

Louie

My First Lady

Hey Mom,

It’s me again. I’m not ready to discuss the day you left this crazy world. I don’t know if I ever will. But I want to talk about the time I took you to the White House in 1986 to meet President Reagan and the First Lady. I still think about that experience now and then because it was a joyous event for me as an entertainer and a low point for me as a son.

We were there as part of an all-star salute commemorating the re-opening of Ford’s Theater, where John Wilkes Booth shot and killed President Lincoln. That part of the festivities was bittersweet, too—the renovation was beautiful but in the museum in the downstairs of the theater, there were all sorts of artifacts of the tragedy, including the actual bloody sheets, more than a century old, from Abraham Lincoln’s dying body.

The entertainment was Lance Burton, Victor Borge, Joel Grey, Freddie Roman, Jaclyn Smith, Tommy Tune, and me. It was going to be a TV special—taped, not live. We all performed for the President and First Lady, then went to the White House to meet them—Ron and Nancy! (Christine Baskets is a huge Ronald Reagan fan.) Not bad for a kid from the St. Paul projects, right?

Mom, I’m writing this letter about a very specific occasion that happened three decades ago because I was not a very good son that night. I was mean to you. Yes, mean. Yes, me. I thought what you were wearing wasn’t up to White House standards. But my opinion was a bunch of crap. It wasn’t true. Want to know the sad thing? The dress you wore was just like one that Christine wears. A sundress, in fact quite a beautiful one. It was absolutely up to standards. I was being a jerk. Why? I don’t know. I still think about my mean-spirited, childish behavior that night.

Why would I be cruel? Because someone was cruel to me. And when someone is cruel to you, the cruelty has to go somewhere. If the cruelty happens to you when you’re a child, a developing person, the cruelty gets in there, does all kinds of damage like a ricocheting bullet, keeps ricocheting around in there, and if you don’t deal with it, if it isn’t add

ressed and resolved, if you can’t figure out why the cruel person is being that way to you, it will cause lingering resentment that just keeps ricocheting. So, Mom, that resentment came from someplace deep inside me, and I’m sorry that it got out, because you didn’t deserve that ricochet hurting you.

I wish I had a less disappointing explanation for my actions. But even with an explanation, I still wonder why I would ever hurt you, the sweetest person I’ve ever known, the best mother ever. I can’t undo how I acted then. I can only say I’m so sorry for being cruel to you, for the stupidity and carelessness of it. To this day it breaks my heart because I’m sure it broke yours. The best thing is, I know deep in my heart that you forgave me. If you could forgive Dad, then you could do it with me, for that.

Mom, I had the bullet removed, finally. That resentment of Dad. That resentment is gone.

And I know I’ve done kind things for you. I know that. Jimmy told me that when you were a young mother, before I was born, you would say things like, “Someday I’m going to go to Europe, and I’m going to have this and I’m going to do that . . .” And he would say, “It’s never gonna happen, Ma” (though he told me he felt really bad afterward that he dismissed your dreams like that). And with each kid you added, the chance of your doing even one of those things got smaller and smaller, then tiny, then looked like it disappeared altogether. And then, in the late 1980s, I took you to England. We had lunch in Paris. I bought you a nice car. I took you to the White House. And at least some of those experiences and possessions you had always wished for, happened. I’m glad I could do that.

Still, please accept my sincere apology for my senseless behavior. Mom, you were and always will be my First Lady.

Your regretful, careless, and occasionally even cruel tenth child,

Louie

Louie and Tommy

Thank You, Brother

Hey Tommy,

Thanks for helping Shanna & for all you do for me & everyone in our family. What you did for Mom, Billy & Sheila. Thanks for thinking about me. I can’t wait to see you when I’m back in town for New Year’s Eve & also when you visit me again. Life is short & we should cherish each other all the time &, like you, be willing to help!

Miss & love you, Truth Ranger, a.k.a. my Brother Thomas Todd Anderson!

Love,

Brother Louie

Truth Ranger

Hey Mom,

I’ve been texting a lot with Tommy, since we live far apart. I love texting because it’s a great way to send a really quick message to someone, which they’ll usually see pretty quickly, if not immediately. It doesn’t take the time of a phone call and doesn’t demand the other person be available when you send the message. It has an intimacy. I love that Tommy and I can communicate in this way, especially since I’m in Las Vegas or Los Angeles or traveling and he’s in Newport, just a few miles down the Mississippi from where we grew up in east St. Paul, and it’s too rare we get a chance to be in the same place together. But I try. We try. I loved and love all my sisters and other brothers—but Tommy and I are two years apart. He’s been my best buddy, the sibling I’m closest to. The baby of the family. Number eleven of eleven. He and I were two peas in a pod, as Laurel and Hardy used to say. You know all this, Mom. He’s funny, and he loves to tinker, and he’s impatient, and he rolls his own cigarettes, and he’s a hoarder (like us), and so generous, and really smart and such a good friend and he’s bipolar and a little paranoid, and I used to “tiny talk” at him when I was mad at him because he was the only sibling who was younger than I was and who I could sort of bully, and later I made that part of one of my routines. He will always be my baby brother. I have given him at least two hundred tiny bottles of shampoo that I have taken from hotel rooms. He was so sweet and good to move back to the Twin Cities to help with our sisters.

The last couple years Tommy’s been signing most of his texts to me with “Truth Ranger.” He came up with an idea for a children’s show called “Truth Rangers,” which would encourage kids to always tell the truth. There’d be some adventure and the outcome would be a lesson about truth or lying or just life. He always puts the phrase in quotation marks, though he’s used it so often by this point, he could just drop them. No one’s gonna sue.

He’ll text me anything—that’s what texting does for you, Mom. Anything and everything seems worth sharing. A few examples from Tommy to me:

Stay away from the dollar store, you won’t be able to stop yourself. Haha!

My neighbor Kelly knocked over the computer monitor/TV which was held up by a gallon of black enamel paint!

Have to perform brain surgery on myself! Just need one more mirror! -“Truth Ranger”

I think it’s the little things at least as much as the big things, maybe even more than the big things, that remind me to be present and grateful. I love having a younger brother.

Love,

Lucky Older Brother Louie

(a.k.a. Truth Ranger’s sidekick)

New Year’s Eve! (Minus the Booze)

Dad and Mom

Hey Mom,

Tonight is New Year’s Eve 2015, almost 2016, and for each of the last twenty-five years I’ve hosted a special kind of New Year’s Eve bash. Now, we do it at the Ames Center in Burnsville; before that, it was at Northrop Auditorium on the University of Minnesota campus.

So what makes it special? Starting the year after you died, I decided to begin each New Year honoring you. How? By having no alcohol served at the venue where I perform, because we grew up with a father who was always drunk and who made us live in fear of his drunken behavior. And of all of us, you had to deal with it most of all. So I wanted one night, in fact the night most associated with alcohol consumption, when people who do not want liquor in their lives could go someplace, have a great celebration, and not worry about drinking or being around people who are drunk. The Minnesotans and tourists who come seem to really love it. My goal tonight, like every time I perform but especially tonight, is to make people feel as if they’re going to pee from laughing so hard. There you go . . . let it go . . . I don’t want a dry pair of pants in the house.

On a dry but really, really cold, good Minnesota night.

The truth is, Mom, I wish we could have gotten away from Dad, the raging alcoholic. I wish we were strong enough. I wish you were strong enough. Can I say that? Is that another way of calling you weak? I don’t mean that. And what would we have done, anyway—live year-round on welfare? Obviously you had something you needed to complete with Dad, something you felt you just couldn’t give up. What was it, though? For one reason or another you thought that, in the end, we were better with him than without. I’ll never really know. I understand that you had all these kids, and you must have told yourself, Well, at least I know what I have with him, and maybe you told yourself that there are worse men out there, and maybe you would have ended up with that man, or no one. I understand that it would have been a very hard road to leave him, if you had actually seriously considered it—there weren’t shelters then, places to hide out, to go for support, to leave the kids for a while, as much as there are today. (Though there should be even more of those today, and better support and services.) I understand how hard it would have been because once you’re on a well-worn path, it’s “easier” to keep treading on it. (I put “easier” in quotation marks because it’s a lie, Mom, it isn’t easier.) But that path you’re staying on, that we stayed on—we knew for certain it had monsters on it. We had seen them. We would see them again. They were always just about to jump out. And if the alcoholism “changed,” as it did with Dad, and it no longer ignited into violence, well, it morphed into something else later on, a simmering meanness that was often worse than an outburst, because with an outburst you at least knew it would be over quickly, and you’d get a reprieve from the pain. (That’s a lie, too.)

To this day, Mom, I still think about the drunken abuse Dad doled out to you. Hitting you, calling you a whore. There’s a helplessness we all felt.

Maybe you stayed with him because you loved him and you knew that if you worked really hard or prayed enough or loved him enough, that he’d be able to turn it around. I’ll stick it out and do the best I can, keep moving forward and maybe something good will come around the corner. You were the most optimistic person or the most stubborn or the most determined, maybe all three. You “won” in the end because he quit drinking—but he never really changed. And then he got sick, and physical health or the lack of it is the great equalizer, and when a loved one gets sick, everything else takes a back seat and looks meaningless by comparison. Then it’s just about survival.

But why not emotional and psychological sickness? Why don’t they stop us from what we’re doing, so we can address that? Must it always be cancer before we press the PAUSE button?

I know, I know. More questions that can’t ever really be answered. But I had to ask.

People talk about how drugs ruin lives, and they do. I’m not downplaying how terrible drugs can be. But marijuana’s legal now, at least medical marijuana, in some states. I’m all for it. It makes more sense to legalize weed than alcohol. Let’s legalize marijuana in all states, and not just for medical purposes.

Because we all need something to help us get through the pain. I get that’s why people drink. Weed is a lot better. Then again, fans and friends used to come up to me after shows, wanting me to smoke pot with them, and I told them, “Do I look like I need another reason to be hungry?”

The fallout from alcohol use is far worse than from marijuana use. I don’t have the statistics. I just know that alcoholism still affects my life, and Dad’s been gone almost forty years. I know that when you grow up in an alcoholic family, it’s kind of like an atom bomb or a hydrogen bomb or any of those bombs where no one gets out unscathed. You’re affected at the time, and also as time goes on. Its effects seep into your life, affecting everything you do, from the friends you attract to the risks you take or don’t take to the whole life you try to lead.

Hey Mom

Hey Mom