- Home

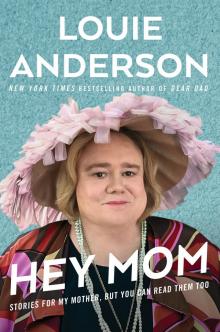

- Louie Anderson

Hey Mom Page 4

Hey Mom Read online

Page 4

The way you set the table, you’d think the President was coming over. Little salt dips for the radishes, oil and vinegar cruets, cloth napkins. If for no one else, Mom, at least it was for you. You found a way to live richly in poor conditions. High-class all the way.

I miss those little things—but now I don’t really have to miss them because I reenact them on TV.

Love,

Louie

Each Parent Got a Book

Hey Mom,

We have a break in filming Baskets, so I’m doing a few dates in the Midwest—Traverse City, Michigan, and Worthington, Minnesota. At my last couple of shows, several people came up to me to talk about my book about Dad. It’s been almost thirty years since it was published but it really strikes a nerve with some people.

When Dear Dad came out I received more than ten thousand letters, letters that were really emotional, sometimes heartbreaking, from readers who felt as if they were reading their own story in my struggle to understand a difficult, frequently cruel alcoholic parent. One letter writer actually visited Dad’s gravesite, at Fort Snelling National Cemetery, just like I did at the end of the book. “I hope you don’t mind,” the person wrote. “I felt very close to you and your family after reading your book.”

Mind? How could I mind? It was a beautiful sentiment. It’s comforting to find others like me. Alcoholism is a silent assassin that keeps attacking long after the attacker is dead and gone. We keep feeling it. Forever. Trauma is trauma, Momma, and I thank you for standing in front of the blast, time and again.

Another letter writer wrote that, in the same way Dad was with us, his father “never told me anything at all about his childhood, and I thought that odd. People from that generation were different. Their lives were different. The world also was different.”

That’s true. Dad’s unwillingness to share moments from his terrible childhood and from the war—a lot of that could have as much to do with generational style as with who he was or what he suffered. Or maybe it comes down to a really simple idea: Who wants to revisit the scene of a crime? Who wants to revisit what they felt they had laid to rest? But you know, Mom, it’s always right there, the source of the pain. It’s right there, within reach. You have to stare it down, back it into a corner, say, You have no power over me, until the monster is no longer a monster, it’s just a little pea in a pod and that little pea can’t affect you anymore. Only fear and anxiety allow the pea to grow into a boulder.

Another letter writer, David, a self-described “fat ACOA,” wrote that “Your life and mine have taken different paths, but the feelings you describe are the same as mine. I am tempted to send the book to my father. Maybe I will.” I hope he did. On the other hand, a letter writer from Massachusetts wrote, “You’re looking for answers, Louie, but there might not be any.” If she’s right, that will be very frustrating. But she’s probably right. Right?

Am I supposed to stop asking questions?

One letter writer asked a question about his recently deceased alcoholic father that I never asked of Dad, but now I’m obsessed with it: “I could not help wondering, What was it like at the moment of that last heartbeat? What was his very last thought?”

Me too. Was Dad’s last thought, Hey, I’d love to have one more drink?

Was it, I’m sorry?

Was it, Ah, shit . . . that’s IT?

Maybe the last thought was relief from a lifelong fight with his own demons and dragons. His boulder. His mother and father. His father’s father. Maybe it was memories of a childhood whose chance for more happiness ended so abruptly.

One twenty-one-year-old woman, with a double whammy—both parents were alcoholic—wrote to me, “The big thing that I am not getting over is the guilt and self-esteem thing. I can’t think of myself as worthwhile although I’m ready to. I have had enough of this life.”

This woman has a baby son. She sells shoes at Sears, in a mall. She has struggled with food and weight issues, too, bulimic for years. Her husband is a recovering alcoholic. Her father is in denial about his alcoholism.

Yet she writes to me things like, “I really want to tell you about [my husband’s] relapse. It’s the kind of morbid-funny humor you might like.” And “I’ve been in treatment and everything—it’s all really laughable!”

Isn’t that remarkable, Mom? How can people still do that, after so much pain?

I think part of us becomes addicted to the dread, the drama, the disrespect. We crave it, we need it, we search for it in others and in ourselves. But there’s a switch you have to learn how to turn off, a “discomfort switch”—At least I know I’m no good. At least I know they hate me. At least things are not going to work out. That switch has to be turned off. Sometimes we need to just find an actual switch in the house and turn it off. Any switch. Just find one. Turn it off and say, I’m worth it I’m worth it I’m worth it I’m worth it worth it worth it. We may have to say it a few thousand times before we start to believe it.

I’m worth it, Mom, and so were you.

Love,

Louie

Life Sucks Without Bread

Hey Mom,

Did you know that Minnesota has the world’s largest candy store?

I thought I might get a chance to go there on this trip home but it doesn’t look like it. I’ve never been there but I’m proud that Minnesota’s Largest Candy Store, in Jordan, just south of Chaska, is also supposedly the world’s largest candy store. (Mom, we also have the largest shopping mall in the country, the Mall of America. It opened in Bloomington two years after you died. It gets about the same number of visitors every year as Disneyland, Disney World, Yellowstone, and Yosemite combined. You would have been a regular.)

I remember buying candy as a kid. I got money from you or Dad and went to the corner store by school and bought “silver dollars,” two for a penny—red licorice in the shape of a half-dollar piece, hard and delicious. I’d cram them into my mouth, systematically feed them in as if my mouth were a vending machine. And even when it got full, I’d keep at it and usually jam the slot. And I would just keep chewing and chewing and slowly chewing. I remember my jaw would be so sore because I had to finish the candy before I got home or to school. Maybe I even drooled some, in my lust to eat and finish. I’ve forgotten lots of things from my childhood but I remember that exact feeling.

Is that food addiction? Probably. After all, I’m a food addict.

You know what’s amazing? Even as I write this, I really can feel it in my jaw. The insatiable need for that candy, or really any food, that feeling that I shouldn’t have. That feeling, oh my God I have to have this I will even steal money out of my dad’s pants dig for pennies so I can get that candy. That was my first drug of choice, candy. There was a secret involved. There was shame involved. I was trying to hide it from others. What was going on with me, Mom? What exactly happened to me? Why was I somehow able to take that terrible drawback and cultivate it into a successful career as a comedian?

Because that’s what I did: I turned it all around. I turned it on its head. I used it against myself so that people couldn’t use it against me. I took charge of it. Of the knowledge. I could dole out however much I wanted. I was the controller over myself.

Wow, that’s a little heartbreaking.

At meals I had to be careful about how much food I put on my plate because Dad was watching and he might yell at me for how much I took. “Lard ass” was the go-to insult.

But you gotta have enough mashed potatoes so you can make an indentation deep enough for the gravy to pool.

And you need the corn.

And the pot roast, Mom, which you had been cooking for three or four hundred hours—wouldn’t it be rude not to have seconds? When there are people in Africa and China way poorer than even us who could never afford such a meal? Oh, and you have to take some more of that incredibly delicious gravy, which is meant for the pot roast anyway, so it wouldn’t be right to have pot roast without gravy. (At Thanksgiving, you would make

seven thousand pounds of sweet potatoes, then you would ask periodically, “Did you have some sweet potatoes?” Of course I had but whenever you asked that, how could I not take another helping? Especially when you said, “They’re hot. There’s more in the oven. There’s some in the garage.” That last part I made up.)

And the hot buns.

And the iceberg lettuce, which doubled as a healthy Anderson salad.

And there was always dessert.

And we had our own deep fryer.

When we first got the deep fryer, I remember that we cut up every potato we could find to make french fries. You have to. Then we got more sophisticated and made potato chips, all by hand—we didn’t have any kind of slicer. We were the slicers and dicers. Then we took chicken to fry up but we never really knew what we were doing with chicken. At least I didn’t. We wanted to fry up anything—onion rings, of course, and a whole can of that white lard you used so often, Mom. I thought about throwing a potholder into the fryer to see if it would crisp.

We all have our own drug. Mine is food. It was for you, too, Mom, though maybe not quite as much. The few photographs I’ve seen of you as a child show a plump little girl. And only two of the eleven Anderson kids are, or were, what you could actually call thin. The other nine are, or were, anywhere from slightly overweight to obese to morbidly obese, like Mary and me. Tommy gets up there, too, though he was fat in a different way, “big boned,” a bigger skeleton than mine, built more like Dad. I’m built more like you, Mom, with a smaller skeleton. My fat all pools in the gut and the thighs.

In one way, food is a tougher drug to deal with than actual drugs. In some ways. Not in other ways. For a lot of people it’s still hard to believe that food is a drug. But just like other drugs, it affects us emotionally and physiologically. When I bite into a Carl’s Jr. six-dollar burger, I have a physiological reaction to it, which then alters me emotionally. Maybe the high isn’t as big as the high from cocaine, say, but it certainly changes how I feel. I’m okay now, I’m okay now, I’m okay now.

The other night I had some bread. Now, Mom, I’m trying to not eat bread these days, so that’s got to be something of a surprise to you. But the restaurant had gluten-free bread and I knew I could have that. Gluten-free bread has no wheat and it’s the wheat that really affects me. So I took some lean turkey, put it on the gluten-free bread, bit into it and I was like, Oh, I get it—It’s not just gluten-free but taste-free, too! So disappointing. The only way to eat gluten-free bread is to toast it, butter it real good, then put jam on it, until you’ve eliminated the whole point of the gluten-freedom.

And here’s why in some ways food’s the hardest addiction: food addicts can’t ever completely avoid their weakness. We need food to live. Yes, I should eat healthy, organic, fresh, non-processed food . . . but I’m still always skirting disaster. You don’t tell a crackhead they can still go to the crack den, just don’t have any crack. When I drive past a McDonald’s, am I supposed to pretend I don’t see the golden arches? Pretend it’s just a yellow statue of butt cheeks and move on?

AND HOW MUCH STEAMED BROCCOLI CAN ONE MAN EAT??!

Sometimes it feels as if the only thing I’m allowed to eat is steam. Eventually I would like some cheddar cheese in my steam.

I try to eat healthier, Mom, but I came from an unhealthy family. And I still feel as if healthy food has a ways to go.

“How much are the organic bananas?”

“Two ninety-nine a pound.”

“And the non-organic bananas?”

“They’re free.”

“Give me the free bananas and some organic stickers.”

I have trouble with some of the other labeling, too, like “free-range.” What does that mean? It means that instead of being cooped up before we kill them, the chickens get to run free before we kill them. But you know the cooped-up chickens are trying to warn the free-range chickens, sticking their heads up against the wire windows, calling out, “You’re living a lie, Betty!”

Actually, it’s not food that’s my drug. It’s bread. Life really sucks without bread. It does. Growing up Anderson, it felt like, if there’s no bread, there’s no meal. Here, today, I was having a great day, Mom, I took care of myself, I exercised, I ate healthy, then I went to meet some friends at a restaurant and they brought us a loaf of really, really good Italian bread with an incredible crust . . . If I were put on a desert island, I would just want a giant baguette and a keg of butter. That sounds so great, actually. I bet you think so, too, Mom. Remember I used to joke about how “my mom ate every piece of butter in the Midwest”?

I had a dream the other night that I had died. I was taken to the funeral home and they embalmed me with butter. When they went to place me in the casket, it was a giant baguette. They slid me in, cut a hole in the top, and a breadstick was holding the top of the casket open. People were walking by me, paying their respects and saying, “God, he smells good.” One person even grabbed a hunk of the baguette casket as they walked by. The only problem is, they left my shoes on. If you’re going to slide me into a baguette casket, remove my shoes.

Life sucks without bread.

Warmly, with butter,

Louie

Louie Anderson Is Dead

Hey Mom,

When we finish filming Season 1 of Baskets, I’m sure I’ll feel a little let down. Hopefully we’ll get renewed for a second season, but either way, I’m grateful for the experience. I try to appreciate every moment. You never know when you won’t be able to anymore.

I was dead, once, for a few hours.

About six years ago, some jokers decided to pull a hoax that I had died. Not just me but Britney Spears, Jeff Goldblum, Harrison Ford, George Clooney, Miley Cyrus, Natalie Portman, and Ellen DeGeneres, too. We had all died. The idea was to spread the news on the Internet. (What’s the Internet, Mom? Okay, it’s basically the world now, the “place” where we spend most of our waking hours, even though it’s not really real, or it is real but most of us don’t know where it is. It’s a place where you can do lots of things, including things you didn’t even particularly want to do, and learn odd things, like that you’re dead when you’re not. It’s just like the actual world, Mom—hard to explain.) I can’t remember the cause of my death but Jeff allegedly fell from a sixty-foot cliff while filming a movie in New Zealand; Harrison allegedly drowned in a capsized yacht in the Riviera; and George allegedly died in a private-plane crash in Colorado. So I was dead, we were dead, to at least a bunch of strangers, until we started piping up that we weren’t. I don’t know how many people have to believe a hoax for it to be considered a success, but for a while, if you googled “Louie Anderson,” maybe the fourth entry that came up was “Louie Anderson is dead.” (What’s Google, Mom? You know when you couldn’t remember some actor’s name or the name of the shopping center with the Red Owl grocery, and you’d call your friend Monny because she always knew all that stuff, or you could remember only the names of two of the ships that Columbus sailed, the Niña and the Pinta, but not the third? Well, imagine there’s a place you can type in your questions, and you don’t even have to type them in question form, just use a few key words, and suddenly, before you can even get your eyeglasses on, it’s telling you that it was Robert Mitchum, Phalen Shopping Center, or the Santa Maria. That’s what Google is—a thousand Monnys out there and more, millions of them. Google is the person in the neighborhood with all that information, like Monny, but also the nosiest person, kind of like Darlene. You remember Darlene, Mom? Three doors down, always had her nose out the window? Because not only is Google answering your questions but then it’s getting inside your head to figure out what you might think of next before you think of it. Were you asking about sparkly shoes? The next time you go on your computer, you’ll see an ad to buy sparkly shoes. So it’s sort of like Monny times a million plus Darlene, if Darlene were Big Brother.)

Anyway, when the hoax about my death turned out to be just a hoax, lots of people on Twitter tweeted me,

Louie, I thought you were dead, and I would reply, Hold on, let me check. I guess I can’t be that mad at the hoaxers because I got a rare gift: the chance to experience what it’s like to have people think you’re dead, then they realize no, you’re not, then you enjoy this outpouring of genuine feeling and relief, with them calling or writing to say, “Oh, Louie, I’m so happy you’re still alive!” Me too! I liked being dead for a little while. Kind of like Tom and Huck standing at the back of the church listening to their own eulogies and the whole town weeping for them.

(This is Twitter, Mom: Imagine you’re in class and you write a note that says “I like your new shoes,” and pass it to your friend Ruthie, and Ruthie writes something on the note but instead of passing it back to you she passes it to someone else, and it goes around the room, and when it finally gets back to you, your note not only says “Thank you” from Ruthie but it also has a lot of comments from classmates saying that they love her shoes, some that say they hate her shoes, and also some mean comments about you, from classmates who don’t really know you that well. And while the comments are all signed, some of them have names that are clearly made up, like ImAnIdiot or RobinsonCrusoe3rd or SoHungry. Mom, here’s the thing about the Internet, Google, Twitter, and a lot of other inventions that weren’t around when you were: they’re all versions of things that existed only we’ve added electricity to them, which in some ways made them better and in other ways ruined them.)

One nice thing about coming back to life is lots of people got back in touch with me.

Louie Anderson is not dead.

I want to be with you, Mom, I really do.

Just not yet.

Still kicking,

Louie

P.S. I’ll write to you about the day you died, for real. Just not yet.

No Family Feud

Hey Mom,

Hey Mom

Hey Mom