- Home

- Louie Anderson

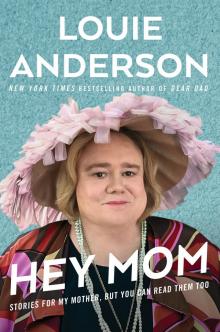

Hey Mom Page 17

Hey Mom Read online

Page 17

She was in her twenties, a young woman with beautiful purple braids. I told her I loved her hair. The flight was delayed. In the old days, a flight delay would have made me all Damn this! and Screw that! Instead, we talked. Mia was her name. She seemed nervous about flying. She was in phone sales. At one point I went to the newsstand to buy some bottled water and see if they had anything healthy to snack on, and I asked Mia if I could get her something, not too pushy, though, and she shook her head sweetly, sadly, Thank you, no. While I was at the newsstand I looked back and saw that she was drinking some sugary-type drink, and sneaking a bite of an Almond Joy while scrolling through her phone, and I imagined myself returning from my errand and going right up to her and reading her the Riot Act and asking her if she would go to my 12-step meeting with me—but when I returned I said nothing. I gave her a hug as we boarded the plane. After we landed at O’Hare, I saw her again. “There you are,” I said. “You made it.” I thought of asking her if we could take a picture. “Mia, I’ve always loved that name. You know why? Because I’m always thinking of mee-a.” It made her laugh. I thought about asking her to exchange emails, thinking maybe I could be helpful to her, but it seemed too forward. I should have.

This is my new life. Maybe I’ve always been this way but now I’m trying to be more proactive about it. Ours is the burden of food and for all my struggles, I thought I could maybe help her find her way out. She was probably suffering beyond belief. And no one really knows what to do about it. It moved me, to meet and talk with Mia. I don’t think I’m seeing these people by chance. I don’t know what anyone or anything is telling me—full moons or fat hummingbirds or colors swirling in the bathroom light, or you, Mom, now almost literally guiding me every time I dress up as Christine . . . but I feel there’s some reason for all this.

Anyway, Mom, you would do the same—compliment someone on her hair, what a nice dress she was wearing, what a pretty smile she had, and then just make friends with her. Were you just getting to know them, Mom, or did you see something in them that you needed? Or see something in yourself that you thought they needed? Regardless, it’s who we are, Mom. We can’t control it. We’re suckers for people. There’s nothing we can do about it. We’re people pleasers. There isn’t anything else, really. That’s why everyone watches TV and movies: whether the story is real or make-believe, we’re interested in seeing what happens to people. Because we’re all trying to figure ourselves out.

What a cruel world we live in—that someone has to be three hundred or four hundred pounds. That’s the drug of this generation. I always see the bigger people in a way that many others don’t.

Some people don’t have easy lives. They just don’t.

I think a lot of women are sad.

Men, too, of course. But I see the sad women out there, mostly because I’m playing Christine.

I watched Mia walk away, in the direction of baggage claim, walk slowly but still more spryly than I walk now, because she still has youth on her side. The sorrow sparrow landed on my shoulder.

• • •

Here’s my goal with Christine: A lot of people know a Christine. A lot of people are Christine. Mom, let me share an email a viewer sent me this morning.

Good morning, Mr. Anderson. I’m writing to thank you for all you do, you’ve always made me laugh. I really needed it. When I was going through a hard time, your character on baskets (AKA christine) lifted my spirits, somehow you channeled my mom, which really made me happy, because she’s not with me anymore, which I needed.

I loved that “AKA.”

I get stuff like this every day—posts on Facebook, tweets, messages on Instagram, emails. Some of it is devastating. Some of it is inspiring. Often I can’t separate the two.

I really want to help people, Mom. I want to be nicer to everybody, not just when they have sorrow (though sorrow is always lurking, always). That’s what you were all about, being kind all the time, no matter what. There’s a chain reaction to being kind. People showed up at your funeral that none of us knew about, or they said they’d met you only once. They just wanted to be there. For you. For themselves.

A few years ago, when I went on the TV show Splash and faced my fear of heights, I think it gave some others strength. Not think, I know. Because lots of people came up to me in the months after my episode aired and told me things like, “I learned to swim because of you,” “I started to swim again because of you,” and “I started to face some of my fears, thank you so much, Louie.”

I try my best always to put myself in everyone’s position, Mom. At the hotel, the room service gentleman lugs a cart full of orders, doing his best to get everyone’s right. This one wants to have his coffee with this kind of cream, that one says can you make sure I get a spoon I like, is there a fork in there, can you make sure the food comes up hot, can you make sure the ice isn’t melted, you call this an entrée, this is really all the damn shrimp in the shrimp cocktail . . . Suppose I’m the twelfth person he’s dealt with today, Mom. Has he had an easy time of it? Are those carts easy to move around? How can they be, with hotel carpet that thick? He just wants to get in and out of each room and each encounter, do his job right, and move on to the next. You can’t blame room service people. They enter each room like they’ve been jumped or attacked before. So I put myself in his place. I say, “How is your day going? Are you busy down there? If anyone is giving you a bad time, tell me, I’ll go down and talk to them about it.” Why not put myself in the position of empathizing and understanding, since I so easily could be in that position? It could be me who’s delivering the food and, frankly, wants to eat some of it on the way up. Does the guest in Room 1405 really know he’s supposed to get four little muffins with his breakfast, not three?

The maid comes in to make up the bed and I actually want to make my own bed, because since I started with the 12-step program I’ve been making my own bed, decided to stop asking people to wait on me and start taking care of myself because if I don’t, then I’ll have lower expectations of myself. So I ask the maid, “How’s your morning going?” She’s taken aback. She smiles. We talk. She has a daughter applying to law school. I tell the maid I don’t need anything, not even the bed made. “No, not even?” she says. She looks alarmed. I assure her it’s okay. She asks if she can punch her code into my room phone to show her boss she’s been to the room. “Punch away!” I say, almost giddy. “Get that code in there!” I asked her for the code so I could punch it in every day, so she could just skip my room. She just smiled.

You aren’t what you eat. You aren’t what you say. You are what you do.

I feel like right now I’m the best Louie I can be. I can get even better.

Good night, Mom. I don’t feel sorrow right now.

Love,

Louie

Defending Champ

Hey Mom,

In my heart, I think I can win it again.

Everyone already has Alec Baldwin winning this year’s Emmy for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Comedy Series. And the Donald Trump impersonation he does on Saturday Night Live is great, really. (Remember what you used to say about Donald Trump, Mom? He’s president of the United States now.) Alec gets the “watercooler” buzz because his appearances are commentaries on what happened in politics that week, even within the previous day or two. Since Hollywood is not very happy with Donald Trump, the Emmy voters might want to say something with their choice. We’ll see. Every Academy voter is supposed to watch one episode of each of the nominees—in my category that’s Baldwin, Tituss Burgess (again) on Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, Ty Burrell (again) on Modern Family, Tony Hale and Matt Walsh (again, again) on Veep, and me. All of them are truly outstanding (that sounds like I’m already giving my acceptance speech). We submitted the “Denver” episode to show my work as Christine. I think it’s a great episode, some really beautiful work with Alex Morris as Ken. After discussing with her mother the idea of meeting someone to date, Christine decides to take a chance and overcome her

fear of rejection so she doesn’t end up alone, and can live a little, maybe even twirl a little.

Even if I don’t win, I’m content with what I’m doing. I know I’m just playing who this woman is.

And I have to reflect on how glad I am just to be working.

Ahmos, my manager, will accompany me this afternoon to the Emmys. You only get two tickets. I wish I could take you, Mom. If you were here, you’d sit next to me and we’d have to buy a third ticket for Ahmos, for seven hundred dollars. I’ll probably also sit near Zach, who was nominated this year for Outstanding Lead Actor, which he deserved. He really deserved two nominations, since he plays Dale Baskets and Chip Baskets. I told him last year he would get nominated this time. He often plays a funny person but there’s such depth to his characters and such breadth to his talent. He never telegraphs what he’s going to do. His unbelievable work in Season 2 made me work harder and strive to do more.

Anyway, Mom, wish me luck—again . . .

Love,

Louie

The Day You Died

Mom and grandchild

Hey Mom,

It’s the letter I’ve been thinking about and dreading since I started writing you letters a couple years ago. Maybe you’ve been dreading it, too, mostly because you feel my pain. This is the worst, hardest letter I will write. But we often have to do the things we hate, right? So I need to do this.

I thought you were going to live forever.

The day a mom dies is the day her child’s life changes forever. It’s the first time you really, truly feel mortality, because the person who brought you into this world is no longer there. You are forced to confront the idea that you might actually be mortal because up until then you were invincible. You were so very powerful because the person who brought you into the world was there, there with you, and you were both alive, and in your existence you had both always been alive.

But then she dies.

And something in you dies. So I guess that means . . . I could die, you think. When she dies, part of your heart stops beating. Something loosens in you, something that gave you stability and comfort. And now you’re no longer as secure on the stage of life. Now you realize that things could come crashing down around you. When the person who brought you into the world, who wiped your chin and wiped your butt, who was there for you and protected you and shaped you, who gave you an identity when you didn’t have one . . . when you lose that lifeline, it’s like the movie Gravity, and now you’re floating in space and hoping to hell that someone will catch you or you can grab a line that you can tether yourself to. It’s the very first day you feel that maybe you could die.

January 4, 1990, I was in Minneapolis. I had performed on New Year’s Eve and decided to stay over a few days, down at the old flour mill that became a hotel. Which meant the rooms were a little smaller, the hallways a little darker, the windows a little weirder than a hotel built as a hotel. But I was comfortable in my room and fell asleep early.

I woke to a ringing telephone. Ringing and ringing and ringing and ringing and ringing. I didn’t know if it was a real phone ringing or a dream of a phone ringing. I did not know where I was. You know I sleep on my side, Mom, and the phone was behind me, and I did not want to turn over and face whatever it was, whoever it was, whatever reason it was ringing and ringing. Yet even as I tried to ignore it, I was becoming more and more awake, and I looked toward the door and there you were.

Only it was a much bigger version of you, practically a giant figure of you, with what seemed like thousands of beams of light coming out of you, with a thousand scarves flowing and blowing around the room, but scarves that are completely transparent, more like wisps of light than a solid material. Some of the colors I had never seen before, so I can’t even describe them. It made me smile and feel love. I reached my hand toward some of the scarves and colors that were nearest but it felt as if something was touching me, as if I was being reached out to, a way of communicating, but I didn’t know what. I felt a tug, and it was the back-and-forth between whatever was going on between us, and then the horrible hotel phone ringing, the explosive awful clanging punctuated by brief silences.

I rolled over to face the phone and the ringing dimmed. I looked back toward the door and marveled even more at this beautiful vision before me, a you-had-to-be-there moment, a sight I have tried to describe here but I know my description does not suffice. Finally, I put the phone to my ear—and all the light, all the color, all hope rushed out, as if a vacuum from out in the hallway sucked everything inside my room underneath the door.

I was in the dark again.

“Louie? Louie?” A familiar voice. Anderson. Brother. Third.

“Yeah,” I must have said, automatically.

“It’s Jimmy. Mom died.”

I don’t know how long it was before I simply said, “Shit.”

There was another pause, by me, for how long I don’t know. Finally, with a sense of purpose, I said, “Hold on a minute, Jimmy.”

I put down the phone, stood, walked to the door, opened it, and looked down the hallway. I was looking for that vision, that light, that love, that hope that had just been present in the room, now realizing that you had been saying a final earthly goodbye. There was no sign of you.

Yet the hallway was brighter than it had been before, I swear. You had left something behind. Maybe a message. A little hope. Assurance that you had been there, that you took time before you ascended to give me a last loving Ora Zella Anderson hug.

When I picked up the phone again, Jimmy told me the details. You were in your car and it had stalled. Mom, you used to snap your fingers and say, “When I die, I want to go like that.” Well, you died in your car. Fortunately, the car wasn’t moving when you had the massive heart attack. It was over as quick as a snap of your fingers.

• • •

It’s a long life but not as long as I wished. Maybe every kid says that, no matter when their mom goes. You outlived Dad, Mom, by ten years. (He was also twelve years older than you, so your life spans were almost the same.)

When your mom dies, you realize that you, too, will one day die. It finally, really hits home. But in thinking about these really sad things, you eventually realize something else: You’re here, thinking about these things. You’re still here. So that must mean that when things come crashing down around you, you can still get up. You can rise from the ashes, climb out from the destruction. You can still make something happen, something good. It’s possible. Just like I knew how much I did not want to write this letter, and hated the idea of writing this letter, here I am . . . writing this letter.

When Mom dies, you dread doing anything new, anything more, anything else. But you have to. You have to right the ship. You have to right things that are wrong, as best you can. You find strength you didn’t know you had.

I guess I’m glad this letter is over.

Love,

Your thankful child, Louie

To Everyone Who Is a Mom or Had a Mom

Hey Mom—and all other moms and dads,

So that’s about all I have to say. I think I’ve said a lot. (Oh, yeah: I didn’t win the second Emmy. Alec Baldwin, the betting favorite, nabbed it. That’s politics for you!) (No, he was really very good.) (Really!)

I’m glad I took the time to talk to you and send all my feelings and love to you.

I have messages for all the other mothers and fathers out there:

Thank you just for being there. God bless you all.

That’s the first message. Here’s the second one:

Keep doing what you do best. Keep loving us. Keep looking after us.

But don’t stop there. No.

Pick a day where all the mothers and fathers of the world, from end to end, every single one of you, at the same time, walk out the front door of your house, your hovel, your hacienda, your palace, your mud hut, your cottage, your apartment, your yurt, your trailer, your igloo, your houseboat, your room, your tent tethered to a fen

ce on Skid Row—step outside. All of you.

Then, each of you, make sure that each of your sons and daughters is within earshot. Better yet, have them within arm’s reach.

Now, take up the hand of each of your children, and all the mothers and fathers together say this:

“Let’s change the world. Because it isn’t working the way it is. Can we all start with a little more kindness, please?”

For the first thirty-six years of my life, I watched my mother’s genius for kindness. Her talent for making family and friends feel close, and strangers just as close. Her ability to be charitable, tactful, loving, and non-judgmental. I have used these as guiding virtues for Christine Baskets.

Nothing is easy when it comes to people changing. But moms have a lot of power. Dads, too. You are the architects of love, our first teachers, preachers, and cheerleaders, the ones who have seen us at our best and our worst, who know us through and through. And you are going to save the world, moms and dads, by getting the ones you love and who love you to be a little different from those who came before.

Moms and dads have a special power, tremendous and in some ways not close to fully tapped. What if we said we were all going to do it for the moms and the dads?

Because it isn’t working the way it is.

If saying things gently doesn’t make an impact, parents, then try this:

“Hey, everybody, knock it off! Stop treating each other so badly! I expect more from you! I expect you, my son, my daughter, to stop and look around and realize that we are all connected. We are all alike. We are all living on this earth together. And we’re not going back into the house for coffee and cake until you truly acknowledge that! We screwed up, screwed up terribly, but we’re never going to stop expecting better from you. We’re not going to accept less. Because if we do, then the world’s over, it’s the end of the world as we know it. For thousands of years, humankind has not gotten it right. So . . . get your act together! Be the first act that’s really gotten it together! Love more and hate less. Do for others. Make the right decision, which you usually know what it is. Be the person you can really be because we know you have it in you and we can’t go on like this! Wake up, smell the roses, do something for somebody, love somebody, care for somebody. Change direction. If you change your desires, you have to replace them with something, and it should be something that will be helpful to other people, to this world, to this earth, to this universe . . . I’m your mom/dad! Honor me as I honored you! If you can’t do it for yourself, do it for me!”

Hey Mom

Hey Mom