- Home

- Louie Anderson

Hey Mom Page 15

Hey Mom Read online

Page 15

Then there’s the other problem: thinking that time stops. (Switching lanes, I know.)

I’ll get to it. I’ll do it. It won’t be that long. I just have to put some time aside. I’m going to write that book. I’m going to visit that person, I’m going to figure that out . . .

We all say all these things. Then we wake up one day and say, “Wait, what was I going to do?”

I’m just rambling, Mom. What other subjects should I go on about? The college football playoff system? Olives with pits? There’s a lot out there that’s just painful to witness, so I’m cranky, wanting things to be better, people to be better, like you wanted, but I’m not sure they will get better, or can get better. No, that’s not right, they can . . . but will they? Will I? Can I take each day, Mom, and stay on the straight and narrow? Stay on the path that’s healthy? Where I’m not acting hangry? Isn’t “hangry” a great word, Mom? Hungry + Angry = Hangry. I love some of the new words we have today, Mom, like spam (remember we used to eat Spam? Not the kind that clogs up my computer, the kind you used to fry up in a pan), meh, selfie, snail mail, and staycation. I prefer a laycation myself. That’s where you go from one place where you were lying down to another place to lie down, and so on.

Was I complaining before? Should I stop it? Wasn’t that one of the promises I made to myself?

No matter what we try to do, if we’re not careful we always end up back in the trough. Back at the Dairy Queen, back at the Soft Serve, back at the Slurpee, back at the nacho bar.

Is this about me or everyone?

Big questions, Mom. I should just stick to the basics. Keep it simple.

Parents should love their children.

Children should enjoy being young.

When you hit forty, you should climb something, anything, because soon you might not be able to.

The things that taste best are always the worst for your health and should be eaten in moderation except in times of extreme anxiety.

And women should be in charge of everything. Honestly, Mom, I feel that way. If women were completely in charge, or way more in charge than they currently are, first hunger and then homelessness and human trafficking would be eliminated. I bet drug-related crimes would go down, too. I just feel that. Clean water for one and all. Everyone would have clean clothes, clean underwear. Three squares a day. Every toilet seat would be put back down. Everybody would have to go to bed by nine o’clock.

Looking at myself, too,

Louie

Big Underwear

Hey Mom,

One day I was pulling clothes out of my dryer and folding my underwear and I said out loud, “Damn! These are gigantic!”

And a comedy bit was born.

They were absolutely gigantic. And even though I was alone in my own house, I imagined all of this happening in a community laundromat, and me yelling, “Are these mine?”

At some point later, I was going through a storage space and came across five or six boxes of underwear. A small city of underwear, because I remember when I was growing up I had just one or two pairs, and I so appreciate that you did the laundry every day, Mom, maybe every couple days at most, so that we would always have clean underwear. And here I have these boxes and boxes of underwear, unused, forgotten. I actually tried to give the underwear away, only I found out you can’t. Goodwill said they wouldn’t take it.

“It’s unsanitary,” the Goodwill guy told me on the phone.

“It’s not dirty underwear,” I said. “It’s not used underwear. It’s new.”

“Sorry,” he said.

Too bad, I thought. Think of all the Louie-sized homeless people that could be using this underwear.

I decided to make artwork out of it.

I decided to make a routine out of it.

I decided I would do a bit about it at the Comedy Store when I was in L.A.

I decided to title my next TV special Big Underwear.

Thanks for always keeping me and Tommy and the rest of us in clean underwear, Mom, when we were too poor to have boxes and boxes of it.

You’re a great mom, Mom,

Louie

When It Rains, It Pours

Hey Mom,

Loss is always just around the corner. It’s part of every life, lying in wait for us. I’ve had this theory for most of my adult life (I wrote about it in Dear Dad): that all we deal with in life is loss. We just keep losing—the comfort of the womb, access to our mother’s breast, the “luxury” to mess in our pants; we lose family members, friends, teachers, neighbors, our hair, our teeth, our speed, our flexibility, our youth. We lose them, don’t get them back, and don’t know how to deal with these losses because we haven’t been taught how. We won’t admit (most of us, anyway) how much it hurts. In many ways, often more subconscious than conscious, we spend all our lives trying to alleviate the feeling of loss, often grasping tightly to things we should let go of. We should always hug each other tighter because of the presence of loss, because loss is there to remind us to live every minute fully and enjoy it like it’s the last dark chocolate buttercream caramel or dark chocolate truffle or milk chocolate pecan/English walnut cluster in the box of Russell Stover candy, to name a few.

Because I had to say something upbeat when talking about loss.

The world is full of sorrow right now, but maybe always. Probably. No, definitely always. I live with sorrow every day because I see it everywhere. Last night I had a job performing for a company that transports individuals and families from one side of the globe to the other. They take you and all your stuff, all the way down to your toothbrush, from St. Paul, Minnesota, to Dubai, or from Paris, Texas, to Paris, France, or vice versa, or from Boston to Austin or Nebraska to Alaska or Malta to Yalta. (Sorry.) Afterward, I had a meet and greet, and took hundreds of photos with people. What autographs were a generation ago, Mom, that’s what these celebrity photos are now. (Did I just call myself a celebrity? Ugh.) Did you ever get any autographs, Mom? Did you get one from Dad that first night you saw him play trumpet with Hoagy Carmichael’s band and fell in love with him? I know you and your mom and your dad listened to the radio as Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic, and we all watched the moon landing on TV together. So anyway, after the show for the moving company, I was riding high, carrying my leftovers and walking to the car they sent for me. I remember how much you enjoyed it when they sent a car for us when I was filling in for Joan Rivers because her husband, Edgar, had committed suicide. Joan was feeling sorrow then and maybe forever after because suicide is a brutal thing. You just don’t know what to do! Who to be mad at. When someone commits suicide, here’s the question I always have: Who did they want to kill? I know Dad’s sister killed herself because of the murder at their house years earlier, which ultimately caused Dad such agony, and his agony caused you and all your children such agony. Do you think it was smart for me not to have kids, Mom? Sorrow is like plastic in the environment: it takes years for it to dissipate. SpellCheck wants to say disappear or dissolve instead of dissipate but I’m not gonna let it, Mom, I’m not gonna let SpellCheck win! Sorrow is like a sparrow: Out of nowhere it can land right in front of you. Though luckily it can also be gone in an instant.

On this beautiful Chicago evening I was feeling no sorrow, I had a great show, people laughing and cheering me on, uplifting comments during the photo taking, from “I’m a longtime fan!” to “I loved Life with Louie!” to “I love your stuff about your parents! I love your mom character on Baskets!!”

At the Waldorf Astoria Chicago, I went up to my room, had some dinner, and decided I needed a shower, to relax. In hotels I always ask for a handicap bathroom because the showers are better to walk into—bigger, less slippery, and the older you get, the more you need a railing. Plus, there’s a chair that folds out from the wall that you can sit on. I turned the water on and just let it run over me. I was really enjoying my shower. There’s something about a really nice hot shower that brings you anywhere you want to go. It gives you a chance to

wipe away some of what’s racing in your mind after a show, an entertainer’s quick path to meditation. I got the show, I got the laughs, I got the check, I got to meet a lot of wonderful people. I knew I was a lucky guy.

Then a creak and a crash.

Before I knew it I had pulled the chair out of the wall and was lying on the shower floor. I rolled over, half laughing and half crying. The water continued to run over me. I was very afraid I might not be able to get up. Here I was, an entry on Comedy Central’s list of 100 Greatest Stand-Ups of All Time, 420 pounds, and I couldn’t even stand up. I was lying on the shower floor, the entire seat pulled out of the shower wall.

My first instinct was to blame someone—but who? There must have been a warning on the chair but I couldn’t see one. What was the top weight the chair was good for—300 pounds? 350? 400? 450? As the numbers climbed in my head, I realized, in that moment, what I had thought I’d realized so many, many times before: I have to do something about this. I felt a range of emotions—embarrassment, shame, fear, rage, self-loathing . . . but really sorrow.

How did this happen? How do you get like this? This was definitely my next journey, I thought, while lying there, water pounding my body. This time I’ll complete it. Sometimes you just know you’re going to do a good job cutting the lawn, washing the car, cleaning the fridge, writing a book report . . . you just know.

It was time. I felt it. Humiliation and desperation are powerful motivators. A lot of people are going to say to me, “You look really good—but aren’t you worried you won’t be funny?”

When I hear that, my answer will be very simple. “No, I’m not worried at all,” I’ll say.

I got up off the floor—I don’t even remember how, though I believe I reached for a towel and grabbed the handles of the shower and somehow got my footing. As much as anything, I willed myself up. And when I stood, I took a good long look at myself in the mirror. I said goodbye to that body. I said hello to my new life. I walked into the bedroom, picked up the bag of M&M’s that I’d taken from the mini-bar and tossed on the bed, waiting to be devoured, and returned them to the mini-bar. No more M&M’s for me. I told myself I was going to try to live on really healthy food and lots of laughs, love, gratitude, and humility.

I’m going to do whatever I have to do, Mom.

Love,

Soaking Wet Louie

12-Step

Hey Mom,

I’m back in a 12-step program. I rejoined last week, on April 15, after a friend said to me, “Hey, Louie, are you gonna just fricking kill yourself? Because if you’re gonna just fricking kill yourself, I don’t really want to be around to watch. If you don’t give a damn about you, I’m not going to give a damn about you.”

I woke up. I mean, it’s not the first wake-up call I’ve had in my life, and I think we all have a lot more wake-up calls than we recognize or are willing to acknowledge. But my friend’s words were pretty harsh and totally on the money. You hate it when people say things to you like what he said to me, especially if it’s a person who cares about you, but it stuck. I have to look at where I am. I want to be around for a while. I want to be the best Louie I can be.

I’m exercising more. I do stuff for my chest, back, both arms, both legs, both stomachs. Three to four times a week, three to four sets for each body part. For a while I’ve had a lifetime membership to Anytime Fitness because I did some commercials for them, and when I’m there sometimes I work with a trainer. When I’m on the road I have this WeGym equipment, this little thing that you pull. I lay it out on the counter of my hotel room and pretend I’m going to use it. Sometimes I keep the door open with it. Sometimes I actually use it.

This time I hope I keep my commitment to the program. I really, really want to. I’m not gonna lie: it’s going to get bumpy, like now, when I’m in a hotel, and there’s a stocked mini-bar and I want to eat all the food in front of me—let’s see, there’s a giant bag of potato chips, gummy bears, peanuts, those damn M&M’s, cashews, three different types of cookies, and that’s just what I can see from across the room. That’s just the stuff that’s speaking to me! I really am only noticing it now. They would be easy pickings, these goodies, and not one of them can do me any good. Not one of them can help me. Maybe the cashews but they’re probably processed in some way. So I have to make that choice. If I wasn’t on the program and in the right space, my mind would bring me back to these all night long. Yeah, I could rationalize having the “healthiest” item, the cashews, but it’s not on my program.

“Is this room service? Can I get some carrots and some celery? And a side of disappointment?”

Mom, I hope this is some kind of turning point. And I need to share it with you.

I mostly wanted you to know that I’m eating healthier, trying to avoid fast food and processed food, and trying to manage what I consume. I build in snacks and make them healthy snacks, like an apple. I’m in a better state of mind, though I know it’s a day-to-day thing. I honestly don’t feel threatened by the hotel candies and cookies.

Though I might just ask them to remove it all tomorrow, for safety’s sake.

Love,

Louie

Fellowship

Dad

Hey Mom,

I’m on my way home from a meeting of my fellowship group, where all of us have one problem in common: food. For me and you, Mom, it was food. For Dad, it was drinking. I like bread way more than I like booze—yet both are made from grains. And both can kill. Are grains killing us all? Are they the most acceptable drug of choice for us Americans? It’s the grain drain!

I remember when Dad went to an AA meeting, and the hopeful feeling as I considered, Is it really possible that soon I could have a nicer, more understanding, loving father? Some of us also went to an Al-Anon meeting (not Dad, though), for the loved ones of alcoholics, because when someone is an alcoholic everyone around is affected—I mean infected. I loved that Al-Anon meeting in particular, and I think you liked it, Mom. It made me feel as if I wasn’t the only one with a drunk for a father.

Dad went to a grand total of . . . one AA meeting.

“I don’t need any fricking help to quit drinking,” he said. I don’t know that he used the word fricking.

To his credit, though he never went to another meeting, he quit drinking. He never drank again after that. Problem was, he totally white-knuckled it. To Dad’s discredit, his behavior didn’t change much. Yeah, he wasn’t as mean, especially to you, Mom, but he discovered new kinds of mean, new kinds of cruel. He was arbitrary about tasks we kids had to perform. There was no way he would be satisfied with the result, no matter how good and painstaking. If you cut the grass up and back, he’d say he’d wanted it cut in circles. Make him a sandwich, and guaranteed you had put the meat and cheese in the wrong order. One day he liked mustard, the next day he didn’t. And all of the demands accompanied by a “What are you, a fricking moron?” I don’t know that he used the word fricking.

We never went to another Al-Anon meeting, even though I liked that first one.

That was more than forty-five years ago, those initial meetings. I’m glad I’m going to these fellowship meetings now. I go at least once a week. It makes me feel less alone. I’m living a healthier life. I’m healing a giant part of me. I’m just sorry it took so many years to really take care of myself.

But better late than never, right, Mom?

What failed with Dad maybe won’t fail with me.

Your healthier & happier son,

Louie

It’s Your Faults, Mom

Hey Mom,

You’re the loveliest person I ever knew and I was so fortunate that it was you I had for a mother. But it wouldn’t be right if I didn’t point out at least a couple of your faults. Okay with you, Mom?

You enabled a lot of Dad’s behavior. Yes, I understand what a difficult situation you were put in, with eleven kids and being poor and the times being what they were. But you were an enabler. When Dad quit drinking at sixty-nine

, you said, “I told you he’d quit.”

I was speechless when I heard that. I didn’t say anything to you at the time. I was seventeen years old and I remember I just walked into my room and sat on the bed and said to myself, or maybe I even mumbled it out loud, “Oh my God, she thinks that she got him to quit, at sixty-nine.”

You sometimes said to me and the other kids, “It’ll get better,” about Dad and our situation, and you knew it was a lie. But you told yourself it was true. You told us it was. And we could see through it.

I understand that Dad lived in denial much of the time—like when he got diagnosed with prostate cancer and refused to get it treated—and simply never confronted his innermost fears, at least in a constructive way that could have benefited his family (and him). I have tried to go a very different route but I’m not sure you weren’t more like him than me.

We were poorer than you wanted to admit, Mom.

And sometimes it seemed as if you wanted to talk only about the kids who were doing well.

You had a vain streak. Not that it bothered me very much, and I’ve incorporated it into Christine’s character, and I think vanity is sometimes overcriticized, because it’s really a cry for dignity and respect, maybe because self-respect is lacking. But you did have your vain moments. Don’t we all? “Louie, how old do you think I look?” I always guessed under because I knew, Mom, that that’s what you were fishing for. I started doing it myself, asking people to guess how old I looked, but quit when somebody got it right.

Mirror, mirror, on the wall, who’s the vainest of them all? Maybe both of us, Mom. (Yeah, everyone is at least a little vain. If they’re not, I don’t trust them.)

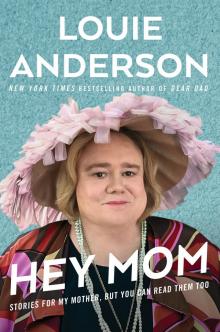

Hey Mom

Hey Mom