- Home

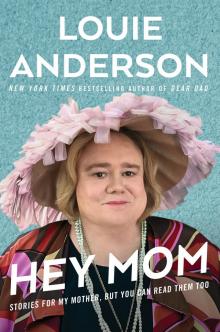

- Louie Anderson

Hey Mom Page 10

Hey Mom Read online

Page 10

You’re always just a nuance away, Mom,

Louie

You Gave Away a Child, or Two

Jimmy and Shanna celebrating their shared birthdays

Hey Mom,

Guess what I got in the mail today from Aunt Shirley? Some brooches that belonged to Aunt Iona. I’m going to pick out the best one and wear it to the Emmys next week. Iona had good taste, like you did. It runs in the family.

You were so good to your sister, Iona, and I’ve always had some questions about that, Mom, which I wish I had asked about in a deeper way when I could have. After you gave birth to Shanna, Child Number Six, exactly a year to the day after Child Number Five, Jimmy, was born, you must have felt overwhelmed. Kent, Rhea, Mary, Roger, Jimmy just a one-year-old—and now one more mouth to feed, more diapers to change. Dad drinking more, growing angrier, becoming more unreliable as a provider. And Iona had had a tubal pregnancy years before and couldn’t have children. Let’s face it, Mom, you were the champ of having children.

When Shanna was six months old, you gave her to your sister so that she would have a daughter.

I know Aunt Iona and Uncle Ike already had an adopted son, Bradley. Shanna went to live with them all in South Dakota, and really wasn’t our sister anymore. She was and she wasn’t. But you know that family photograph from around 1947, where Shanna’s about four years old and they came to visit, and all the Anderson kids are lined up against a brick wall (everyone but Lisa, me, and Tommy, who didn’t exist yet), and little Shanna’s all the way at the end, crying? It looks like she’s wondering, Who are all these strangers?

Mom, how were you able to do that? Was it your idea to give Shanna away? Was it Dad’s? There are so many parts to the story that I still don’t get. Okay, I do and I don’t. I know that Iona and Ike were well-off, and we were poor, and I don’t doubt you thought you were giving Shanna a better life and also making it a little easier on you and Dad and us. Who doesn’t occasionally think of magical ways to make life easier, especially parenting? Then again, you did have another five children after that. Did you ever consider asking for Shanna back? Like, she was more of a rental? I know that Mary had been shipped out to live with them years before but then came back because Bradley and she were fighting terribly, or I probably should say that Bradley was fighting with her, because Mary was unhappy to come back to live with us because she liked her situation there (except for the fighting part). How many kids of yours did you think Aunt Iona needed to feel complete? When you and Dad sent Shanna to live with them, was she just the unlucky one because five kids were tough but six were too many? Or was she the lucky one? Did it have to be a girl?

I know Shanna would visit us during summers and even spent a couple years with us when she was going to school in Minnesota, but she considered Aunt Iona her mommy and Uncle Ike her daddy. Did that ever bother you? Did you ever regret it? Even a little? Shanna told me that when she lived with Iona and Ike, she had it good. She had everything. She had darling clothes and homemade pinafores from Grandma Bertha and the trim of her bedspread and pillowcases was crocheted, and she had all the school supplies she needed, which the rest of us Andersons didn’t, and she had a privileged life compared to us. Compared to a lot of people then. She got to fly in Uncle Ike’s very own airplane, a Piper Comanche, from South Dakota to the Midwestern cities he visited for his business, which was pinball machines and jukeboxes. Sometimes she got sicker than a dog flying in that plane with him piloting, and Uncle Ike brought those bright blue Dairy Queen cartons to keep in the cockpit in case Shanna threw up, but she still had an adventure unlike anything we poor Andersons had back in the projects of east St. Paul.

Which is another part of the story, maybe even the most important part, that I don’t really understand, Mom. Shanna always stayed an Anderson, even though she was raised by Ike and Iona Peiarson, which no one ever spells right even if you tell them it has all the vowels but u (and sometimes y). She stayed an Anderson because you and Dad wouldn’t let Iona and Ike adopt her, though they wanted to. You four grown-ups went for a drive once, and they asked you if they could adopt Shanna, who was very young then, and Dad wouldn’t have it. And you went along with the decision.

I’m not even wondering now about what it’s like to give away one of your kids like that. I’m not judging. Who am I to say what it was to be in your position, exactly then, with a raging drunk for a husband and partner, who was often out of work, and with so many young children. But here’s the thing: Dad didn’t like Uncle Ike! It might have been that Dad was a little jealous, because Uncle Ike was so successful and rich. Or because Dad was a veteran and Uncle Ike hadn’t served, and Dad was so patriotic that he thought less of Ike because of it. Or because Dad himself was given up for adoption and never recovered from it.

But here’s really, really the thing, Mom: Dad would pick on Shanna when she came to visit in Minnesota, because she was living with Ike and Iona, as if Shanna had made the decision at the age of six months to go do that.

Not letting them adopt Shanna really affected her. She got written out of Uncle Ike’s will—technically, he left her one dollar—for reasons she still doesn’t know. (Because she got divorced and they disapproved of that? Because they thought she spent too much money?) And she had no way to contest it because she was an Anderson, not a Peiarson. And maybe Dad was right not to like Uncle Ike—after all, the very last time that Shanna got beaten by her abusive husband, her arm all black from getting kicked, Uncle Ike never said a word to Shanna about it, never a “That’s too bad” or an “I’m sorry,” never said shit. And Aunt Iona would only say about Shanna’s abusive husband, “He’s a very hard worker and makes a very good living and you have a new house,” and all that old stupid stuff that people believed in those days.

It just seems strange to give your child away to another couple, then have serious reservations about them. Or if you don’t have serious reservations, then to not let them adopt and make everything easier.

Just another piece of evidence—what is that, Mom, like, eighty trillion?—that people are incredibly complicated.

So, yeah, Shanna enjoyed privilege when she was growing up but got shortchanged later. Her mom—I mean, Aunt Iona; Shanna called Aunt Iona “Mommy” and you “Mother”—left all sorts of glassware and antiques and labeled them with Shanna’s name; Shanna told me that after Iona died, Bradley and Aunt Shirley had an estate auction and sold all that stuff without telling Shanna. And then when Bradley died, in his obituary it said that he was adopted, and Shanna felt bad for him, because it was the first time she could recall seeing that in an obituary, and she realized how much it must have weighed on him not to know who his biological parents were. Maybe being adopted by a good family and knowing who your birth parents are is the best of both worlds. Weird.

Anyway, Mom, Shanna’s back in South Dakota, after a long time in Minnesota. She left South Dakota years ago because her ex-husband was stalking her. But he died in 1996, at age fifty-eight, when he went out on a wrecker call to pull a van out of a ditch, and it was thirty below wind chill and he just keeled over, a heart attack probably. It looked like he had broken three chains trying to get the van out of the ditch, and probably he got worked up and probably he got really mad, and probably he had drunk the night before, and when he drank, it was to get drunk. Anyway, with him gone, Shanna felt she could return home, the home she called home rather than the one she first came from. She adores her grandkids.

A lot changes, Mom, from the time we’re babies until the time we’re grown-ups. And eras change. But some things don’t change. It’s got to be emotionally complicated, no matter when it happens or why, to give away a child or two, even if you still have a huge houseful of them, even if you’re doing it to help out your sister who can’t have them, even if you think you’re giving at least one of your children a better life and doing the whole thing out of love. Seems a little eeny-meeny-miney.

Or was it just simple, knowing that your sister once said, �

��I always wished I could have kids and my sister had all them kids”?

Since you passed, we’ve all missed you terribly. But I have heard Shanna get emotional and say, “I miss her because I really didn’t get to spend much time with her growing up.” Maybe that’s another kind of missing. I don’t know.

Wondering about the differences

between Mom, Mommy, and Mother,

Louie

Midwesterners

Hey Mom,

How much do we Andersons keep bottled up that other families would have let out?

How much do Minnesotans and Midwesterners keep in, thanks to our famous emotional reserve (the nice way to put it) or repression (not so nice)?

There’s a whole group of jokes called “Ole and Lena jokes”—you remember them, Mom, right?—about Ole and Lena, Swedes transplanted to America, specifically the Upper Midwest. I find them so Midwestern, capturing something very true of that sort of American, stoic and strong and accepting. Here’s one:

Ole and Lena had been married fifty years when Ole died. Lena went to the office of the local newspaper to put in an obituary. She wrote something down on a piece of paper and handed it to the editor. It read, “Ole’s dead.”

“You know, you get five words free,” said the editor.

Lena held out her hand, the editor gave her back the piece of paper, Lena wrote something more on it, then handed the paper back to the editor.

It read, “Ole’s dead, boat for sale.”

• • •

If I had only five words for your obituary, Mom, they would be

Mom’s gone, my heart’s broken,

Louie

70% Disabled, Pending 100%

Hey Mom,

Remember, more than a year ago, when I did a meet and greet at the VA hospital in North Las Vegas, after that “silent comedy” performance I wrote to you about? I sat and spoke with many of the vets and took lots of pictures with them. They’re each amazing and inspiring and beautiful, and wounded, in their own way. Why wouldn’t they be wounded? We ask them to do things we’re not willing to do ourselves. It’s not a video game they’re going into, where you can get killed over and over and come back fresh as new.

The vast majority of those I met were young men—boys, really—who served in Iraq and/or Afghanistan. But there were also some much older vets who had served in Vietnam. They’re all locals, which is why they’re at this VA hospital, why anyone is usually at their particular VA hospital. Not that I have to tell you, Mom, about veterans.

In the end, I sat longest with one young man, Tim, an army tank sergeant who got blown up and whose stomach and leg were all messed up. When you looked at him, you couldn’t see his wounds but you could feel his pain. We bonded. Tim said they weren’t doing anything for him there. His eyes were pleading. I didn’t know how I could help but I told him I would make some calls. I had met someone high up at the USO. I could try Wounded Warriors.

I met Tim’s mom, too. She told me that Tim had had lots of surgeries, with lots more to come. Her smile was the smile of a sad person.

Over the next several months, Tim and I developed a friendship by text. I made calls to the VA and the USO and Wounded Warriors, trying to help address the neglect Tim was complaining about. He was concerned he would be discharged from the hospital’s medical unit prematurely, before they had “a solid plan of care and action” for his physical pain, and that he would be moved too quickly to the in-patient psychiatric unit for the mental health treatment he knew he also needed. Sometimes he apologized to me for texting so much but he wrote that he felt “out of options.” He hoped I would be part of his “team” on his “journey to recovery.” I told him I wanted that, too.

When I could, I distracted him with talk of new comedy material I was developing. He told me he was so excited to see it when it was ready. I think he appreciated hearing about the nuts and bolts of what I was up to professionally.

Once, he wrote that he’d been handcuffed and removed from his room because he had refused to go to the psych ward until his pain was managed correctly. Fortunately, another doctor intervened and said Tim should be returned to his room. I didn’t know why he wasn’t getting the proper medical attention. For starters, he needed surgeries on his knee and foot. He got frustrated because a round of CT scans and X-rays had come back normal, yet he knew how much physical pain he was in. Still, they gave him a “clear to go.”

Mom, how many of us have pain that doesn’t show up on a scan or an X-ray? How many of us have been cleared to go when we weren’t ready? And where ultimately was Tim cleared to go? Back home? Back into the world? Back to a different pain bed to lie in? Only doctors and nurses who themselves have served should be taking care of our veterans, I think, because how can a civilian know what Tim or other vets are feeling? My trauma is sometimes a stubbed toe. I don’t mean to sound silly but I haven’t had my stomach blown up or my legs blown off, I don’t have a face full of shrapnel.

We should be very careful about what we ask people to do for us, especially our veterans. Because they aren’t just our veterans. They’re our neighbors, our friends. They’re somebody’s brother, sister, father, mother, son, daughter, husband, wife. They’re somebody’s baby.

On top of all his other difficulties, Tim was having trouble with his disability claim due to financial hardship. A social worker was trying to help him expedite the claim. But Tim grew frustrated and angry enough to want to file a lawsuit against the VA hospital for malpractice and mistreatment. “I feel like my country is failing me and I don’t know what to do to get the help I need,” he texted me.

At one point, when I thanked him for his sacrifice and courage, he wrote, “I can’t speak for others, but at least for me that’s why I served, and sacrificed so much. For the people of the United States, for you and your family. It makes me feel humble that you and others recognize that sacrifice and want to give back and help us when we’re in our darkest days struggling to live.”

I continued to share small, personal things with him now and then, like when I was coming down with a cold. I thought normalizing things day to day was good.

Throughout Tim’s odyssey, his will was incredible. “I’m getting physically and mentally tougher each day this shit doesn’t kill me!” he texted me. “I see a pain psychologist as well as my PTSD doc 2-3 times a month. I’m now in a pain clinic, and as of this week got my nerve blocking injections for my organ damage, back, knee and foot. I’m praying they just amputate it and let me recover with a prosthetic foot. It doesn’t work from all the nerve damage and it’s just so painful.” He signed the text with his serial number and then “70% disabled, pending 100%.”

Even when things were gray, his communication exuded optimism, and he showed concern for others. “Down 3 organs and my whole left leg is done for—other injuries but those are the worst. I’m alive and kicking brother, they can’t keep me down forever. Hope your cold is going away!” Or “I’m still waiting patiently for my disability to finalize. My mother wanted me to tell you she said hi! I’m sorry for the loss of your brother, Louie. If there’s anything I can do to help please let me know.” Or “I surely need an attorney to take on the big guys. I’m going to make sure what happened to me NEVER happens to another veteran again!”

Mom, we try so hard to be strong but our reserves are not endless, and sometimes it’s easier to be strong for others than for ourselves. Sometimes, exhaustion and misery can’t just be slept off. You can’t just sleep off the experience of war.

After not hearing from Tim for several months, I received this text from his mom:

Louie this is Tim’s mother Renee. I’m contacting you to let you know that Timothy lost his battle with all his pain. I want to thank you for helping him a year ago when he reached out to you for help, that gave us another year with him and he got amazing mental help from all your help. He did not end his life from the mental part of everything, he simply just could not deal with the horrible pain he endured

daily. I just want you to know that that visit made him feel like he was worth something and I will forever be thankful to you for that. Here is the picture of your visit with him that I put in his wall when we laid him to rest. His phone is getting shut off, if you ever feel like contacting me my number is xxx. Also a page was set up for him on Facebook #ourbravestbrothertim if you ever want to take a peek. Thank you again for giving me another precious year with my Timothy I will forever be thankful.

That’s all for now, Mom.

Love,

Louie

Timothy

Penguin Costume Time

Hey Mom,

Today I got the final fitting for the tuxedo I’ll wear at the Emmys on Sunday night.

Beautiful tux, custom-made. It fits great!

Okay, a little perspective. When I tried it on a few days ago, the suit was too big in the shoulders, too loose in the legs, too big in the crotch and the butt. I just don’t have enough junk in my trunk. But the incredibly talented costume designer Amanda Needham, the person who makes Christine Baskets look beautiful week after week, did a phenomenal job. I love what she does.

Hey Mom

Hey Mom